If you had your secondary school education in Nigeria, then you most probably read Chukwuemeka Ike’s The Bottled Leopard. The novel which tells the story of how Amobi, a schoolboy and the protagonist, was chosen to bear the mystical power of his lineage and inherited the leopard power of his ancestors, was among the popular works of literature usually recommended in the syllabus, especially in the junior secondary. Well, 35 years after that publication, the author left his home in Ndikelionwu, Orumba north local government area of Anambra state, to “join his ancestors”.

Before his death on Thursday, Ike unarguably stamped his place in history as one of the most prolific story tellers of post-independence Nigeria, with a lot of iconic works mostly mirroring the African and Igbo societies and all of their uniqueness.

From Toads for Supper — his first work published in 1965 — which deals with the theme of love and the challenge of partners from different ethnic backgrounds in Nigeria, to The Naked Gods (1970), The Potter’s Wheel (1973), Sunset at Dawn (1976), Expo ’77 (1980) and Our Children Are Coming (1990) among others, the late author came, saw and conquered it all regarding Nigerian literature.Before his death on Thursday, Ike unarguably stamped his place in history as one of the most prolific story tellers of post-independence Nigeria, with a lot of iconic works mostly mirroring the African and Igbo societies and all of their uniqueness.

But he was more than that.

‘INTELLECTUAL IN ROYAL GARB’

Not many knew Ike beyond his profile as a writer and novelist. He was one of the top people in the academia who ascended the throne. Until his death, he was the traditional ruler of Ndikelionwu, a position he held as the 11th Ikelionwu of Ndikelionwu since 2008.

During his inauguration, the late author had said he would put all he had acquired to use, including “my national/multinational exposure, my public/private sector experience and my other resources to uplift my town, my people, my state, and my country on a fulltime basis for the rest of my life.”

Top on his agenda at the time was the elimination of traditional practices against widows, ensuring access to micro-credit facilities for his people as well as overall economic empowerment.

During his inauguration, the late author had said he would put all he had acquired to use, including “my national/multinational exposure, my public/private sector experience and my other resources to uplift my town, my people, my state, and my country on a fulltime basis for the rest of my life.”

Top on his agenda at the time was the elimination of traditional practices against widows, ensuring access to micro-credit facilities for his people as well as overall economic empowerment.

INSPIRED BY ACHEBE, HIS LIFETIME FRIEND

Toads for Supper, Ike’s first work was published in 1965, three years after facing a series of rejection. But that’s not all: the work came after he was inspired by no other than Chinua Achebe whom he said was his senior in school.

In a 2016 interview, he told of how Achebe motivated him to start professional writing after he wrote Things Fall Apart.He had said: “Achebe was my senior at Umuahia and he too influenced my writing. In fact, I never thought of writing novels until Chinua Achebe published his Things Fall Apart in 1958.”

Before granting that interview, Ike had confessed that he and Achebe among other friends were focused on writing short stories and that “none of us believed we could write novels” until in the late 1950s.

Hear him: “The novelists we read were from Britain. Though Cyprian Ekwensi wrote then. What actually made me feel that the time had come for me to attempt writing a novel was when my friend, Chinua Achebe, published his Things Fall Apart in 1958.

“We were friends during our secondary school days, university days and even after graduation. The fact that he could do it encouraged me to start a novel. Things Fall Apart inspired me. And by 1962, I had completed a novel, which I titled Toads for Supper. But it took some times of rejection before it was eventually published in 1965.”

In a 2016 interview, he told of how Achebe motivated him to start professional writing after he wrote Things Fall Apart.He had said: “Achebe was my senior at Umuahia and he too influenced my writing. In fact, I never thought of writing novels until Chinua Achebe published his Things Fall Apart in 1958.”

Before granting that interview, Ike had confessed that he and Achebe among other friends were focused on writing short stories and that “none of us believed we could write novels” until in the late 1950s.

Hear him: “The novelists we read were from Britain. Though Cyprian Ekwensi wrote then. What actually made me feel that the time had come for me to attempt writing a novel was when my friend, Chinua Achebe, published his Things Fall Apart in 1958.

“We were friends during our secondary school days, university days and even after graduation. The fact that he could do it encouraged me to start a novel. Things Fall Apart inspired me. And by 1962, I had completed a novel, which I titled Toads for Supper. But it took some times of rejection before it was eventually published in 1965.”

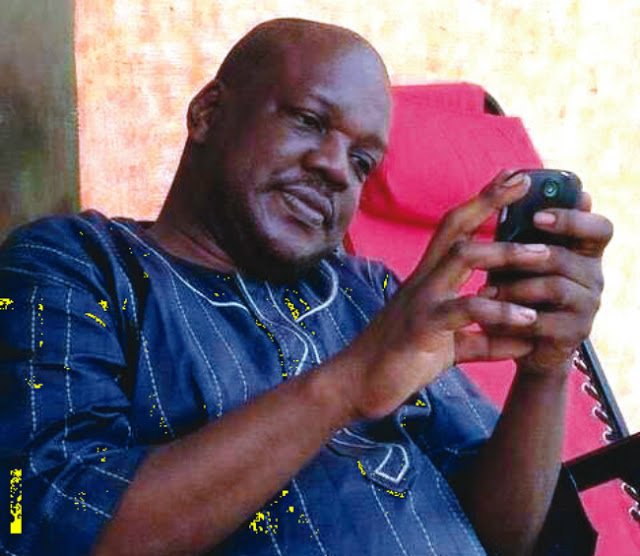

Ike receiving an award from deputy vice chancellor, academic, University of Nigeria, Nsukka

HOW HIS FIRST STORY CAME ABOUT

It was while in secondary school, at Government College, Umuahia; the school encouraged writing and “there was the opportunity for one to publish what he wrote,” Ike recalled.

“Every house had a house magazine. The magazines were handwritten, but later the school had a printed college magazine for the entire school. That was when my first story, a short story titled ‘A Dreamland’ was published,” he said of his first time having a published work.

“Then when I went to the University College, Ibadan, there was also the opportunity to continue with the interest in creative writing. There was a magazine strictly for literary affairs, no student union politicking. You were invited to join the literary club if they felt you had literary interest. The publication of the magazine is funded by the university. I had my stories published in it. So these were the beginnings. After graduation I also had my short stories broadcast on Nigerian Broadcasting Service.”

A THOROUGH ACADEMIC

“Every house had a house magazine. The magazines were handwritten, but later the school had a printed college magazine for the entire school. That was when my first story, a short story titled ‘A Dreamland’ was published,” he said of his first time having a published work.

“Then when I went to the University College, Ibadan, there was also the opportunity to continue with the interest in creative writing. There was a magazine strictly for literary affairs, no student union politicking. You were invited to join the literary club if they felt you had literary interest. The publication of the magazine is funded by the university. I had my stories published in it. So these were the beginnings. After graduation I also had my short stories broadcast on Nigerian Broadcasting Service.”

A THOROUGH ACADEMIC

Ike’s professional career was not only in authorship and leadership roles. In fact, he was in the academic field most of the time he wrote, and long before his first novel, the peak of which was working as the registrar of the West African Examinations Council in Accra, Ghana, in the 1970s.

He began with teaching roles in the 1950s and also served in various other capacities in the education sector, including as an administrative assistant and assistant registrar at the University College (now University of Ibadan) from 1957 to 1960, before proceeding to work as a deputy registrar at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, from 1960 to 1963.

Ike also served as a director at the Daily Times of Nigeria Ltd before working as director of the University Press Ltd, 1978. In 1979, he retired from public service and was subsequently appointed a visiting professor of English at the University of Jos where he worked from 1983 to 1985. He was also at some point the pro-chancellor and chairman of council at the University of Benin, a role he held until 1991.

He is known to have also established the Nigerian Book Foundation to encourage young writers and provide a platform for potential authors.

HIS ACHIEVEMENTS, SAD ENDING AT WAEC

He began with teaching roles in the 1950s and also served in various other capacities in the education sector, including as an administrative assistant and assistant registrar at the University College (now University of Ibadan) from 1957 to 1960, before proceeding to work as a deputy registrar at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, from 1960 to 1963.

Ike also served as a director at the Daily Times of Nigeria Ltd before working as director of the University Press Ltd, 1978. In 1979, he retired from public service and was subsequently appointed a visiting professor of English at the University of Jos where he worked from 1983 to 1985. He was also at some point the pro-chancellor and chairman of council at the University of Benin, a role he held until 1991.

He is known to have also established the Nigerian Book Foundation to encourage young writers and provide a platform for potential authors.

HIS ACHIEVEMENTS, SAD ENDING AT WAEC

After a successful stint as UNN registrar, the late author became the first Nigerian to serve as WAEC registrar. While in that position, he was known to have achieved a number of great feats including cutting the council’s affiliate ties with the University of Cambridge, University of London, Royal Society of Arts, and City and Guilds of London Institute, to become an autonomous examinations council.

His career at WAEC was, however, punctured with allegations that the council under him was favouring southern schools, part of which forced him to voluntarily resign.

Recalling what transpired in an interview with Vanguard, Ike said the allegations were unfounded as “nobody in WAEC, not even the Registrar, knows what any student would score until the results are collated.”

“There was also the allegation that when I was appointed WAEC Registrar, that I did not report to Lagos; that I went to Accra straight. They thought they would catch me but from all the reports, they could not catch me,” he recalled.

“Anyway, I was travelling to Senegal and they wanted me back in Lagos immediately .… At the Airport, somebody gave me a photocopy of the decision they had already taken and the next thing was that Obasanjo wanted me to name any other job I wanted apart from registrar of WAEC.

“I was asked to report to the chairman of the Public Service Commission who said man you are lucky, just name anything big and it will be yours. I told him plainly that I did not want anybody to give me any job. Anyway, after so many intrigues, I offered to retire voluntarily. Sometime later, Obasanjo invited me to join Otta Farms, but I could not. Sometime later, I was invited to be among 15 Nigerians for a special assignment and I also declined.”

His career at WAEC was, however, punctured with allegations that the council under him was favouring southern schools, part of which forced him to voluntarily resign.

Recalling what transpired in an interview with Vanguard, Ike said the allegations were unfounded as “nobody in WAEC, not even the Registrar, knows what any student would score until the results are collated.”

“There was also the allegation that when I was appointed WAEC Registrar, that I did not report to Lagos; that I went to Accra straight. They thought they would catch me but from all the reports, they could not catch me,” he recalled.

“Anyway, I was travelling to Senegal and they wanted me back in Lagos immediately .… At the Airport, somebody gave me a photocopy of the decision they had already taken and the next thing was that Obasanjo wanted me to name any other job I wanted apart from registrar of WAEC.

“I was asked to report to the chairman of the Public Service Commission who said man you are lucky, just name anything big and it will be yours. I told him plainly that I did not want anybody to give me any job. Anyway, after so many intrigues, I offered to retire voluntarily. Sometime later, Obasanjo invited me to join Otta Farms, but I could not. Sometime later, I was invited to be among 15 Nigerians for a special assignment and I also declined.”

LOST HIS ONLY SON TO ASTHMA

The late author was bereaved only four years ago when he lost Osita Ike, the only son of his marriage with Adebimpe Olurinsola Ike (nee Abimbolu), a librarian and professor of library science. Osita had died of Asthma attack on December 17, 2016, at the age of 54.

In a tribute to him shortly after his death, one Uzo Nkem-Mmekam recalled Osita’s jovial personality during their days at the University of Jos.

She wrote: “I remember your booming laughter from our days at the University of Jos and I know that you are laughing your way into Heaven. Sleep well my friend until we meet again.”

Akeem Lasisi, a poet wrote: “Osita Ike was not a literary icon like his father but members of the literary community, especially in and around Lagos, appreciate the fact that he played some vital roles in the sector. He was, for instance, a facilitator of many programmes and events, be it in the book, visual arts and theatre arenas.”

CHOSE 20 NOVELS TO HIS NAME OVER £20M

In a tribute to him shortly after his death, one Uzo Nkem-Mmekam recalled Osita’s jovial personality during their days at the University of Jos.

She wrote: “I remember your booming laughter from our days at the University of Jos and I know that you are laughing your way into Heaven. Sleep well my friend until we meet again.”

Akeem Lasisi, a poet wrote: “Osita Ike was not a literary icon like his father but members of the literary community, especially in and around Lagos, appreciate the fact that he played some vital roles in the sector. He was, for instance, a facilitator of many programmes and events, be it in the book, visual arts and theatre arenas.”

CHOSE 20 NOVELS TO HIS NAME OVER £20M

If you are asked to choose between having 20 novels to your name and £20 million to your account, which would you go with? Well, Ike once said he would go with books in his name.

According to him, “I would rather have 20 novels against my name, than have 20m pounds in my account.”

Why would he say so? His response would make you think he authored 1 Timothy 6:9-10 in the Bible. He said: “I like money, but money cannot be my target in life … there are things that are more enduring than money.”

He was 88.

According to him, “I would rather have 20 novels against my name, than have 20m pounds in my account.”

Why would he say so? His response would make you think he authored 1 Timothy 6:9-10 in the Bible. He said: “I like money, but money cannot be my target in life … there are things that are more enduring than money.”

He was 88.

***

Source: TheCable

No comments:

Post a Comment